Large Scale Image Completion via Co-Modulated GANs

09 Dec 2021 | GAN co-modulation image completion image-to-image translationThis blog is an overview of this paper by Shengyu Zhao et al. published at ICLR 2021.

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) have recently become popular deep learning models for producing synthetic yet realistic images. They have attained state-of-the-art performance on image generation tasks, including image-to-image translation.

Since vanilla GANs do not perform well in free-form image completion tasks (Liu et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2019), there has been significant progress using task-specific approaches to improve the quality of generated images, such as by minimizing color discrepancy. These specialized GANs work well for small-scale image completion tasks, but they do not achieve promising performance when handling large-scale missing image regions. Why might existing models be insufficient for larger regions?

The answer lies in the fact that existing algorithms do not have the capability of generating completely new images. If a model cannot generate a completely new image, then it will have a difficult time completing a large region of an existing image.

To handle large-scale missing regions, Zhao et al. propose co-modulated generative adversarial networks, which use co-modulation to combine the generative capability of unconditional modulated models with conditional and stochastic style representations. They found that co-modulated GANs produce contents that are diverse and consistent with the rest of the image and that generalize well to large-scale image completion tasks.

In this blog, we summarize the approach of co-modulated GANs for image completion, its generalization to image-to-image translation tasks, and a new proposed quantitative evaluation metric for GANs. We also extend the findings by Zhao et al. by performing new image completion experiments to examine the biases of co-modulated GANs.

Overview

- Summary of Co-modulated GANs

- Experiments

- Biases and Limitations of Co-modulated GANs

- Related Work

- Conclusion

Summary of Co-modulated GANs

Co-modulated GANs link image-conditional GANs and unconditional modulated models to address large-scale image completion tasks. Co-modulation brings stochastic and conditional style representations together. To improve existing metrics for image completion, the proposed Paired/Unpaired Inception Discriminative Score (P-IDS/U-IDS) is robust to sampling size, captures subtle differences well, and correlates with human preferences. Experiments using co-modulated GANs lead to high quality and diverse results in free-form image completion and image-to-image translation tasks.

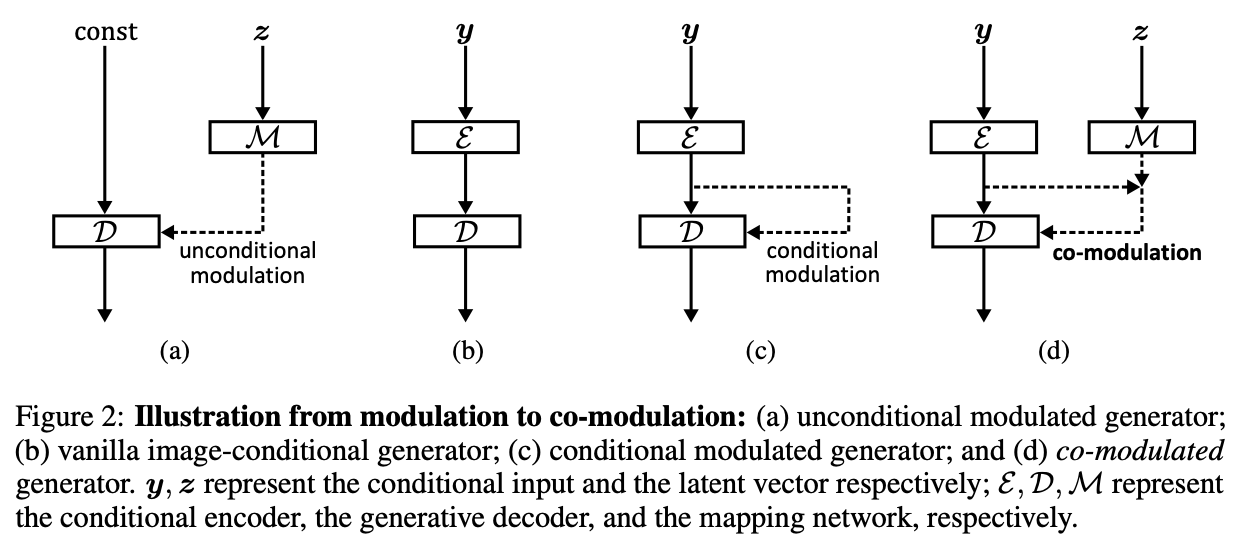

Modulation

In the unconditional modulated generator, the decoder originates from some learned constant, while the latent vector passes through a multi-layer fully connected mapping network. The mapped latent vector generates a style vector for each modulation via a learned affine transformation. The style vector can be expressed as the following:

\[\begin{equation} s = A(M(z)) \end{equation}\]Here, $s$ is the style vector, $A$ is the affine transformation, $M$ is the mapping network, and \(z\) is the latent vector.

The conditional modulated generator extends the image-conditional generator by conditioning the modulation on the learned flattened features from the image encoder. The style vector can be represented as the following:

\[\begin{equation} s = A(E(y)) \end{equation}\]$E$ is the conditional image encoder, and $y$ is the conditional input image.

One issue with conditional modulation is the lack of stochastic generative capability. In large scale image completion, outputs are weakly conditioned, which results in poor generalization and the lack of diverse outputs.

Co-modulation

Co-modulation addresses the generative capability issue of conditional modulation by combining unconditional modulated generators with image-conditional generators.

The co-modulated style vector can be expressed as a joint affine transformation conditioning on both style representations:

\[\begin{equation} s = A(E(y), M(z)) \end{equation}\]The linear mapping in the style vector contributes to stochasticity. Furthermore, the co-modulation approach improves visual quality at large-scale missing regions.

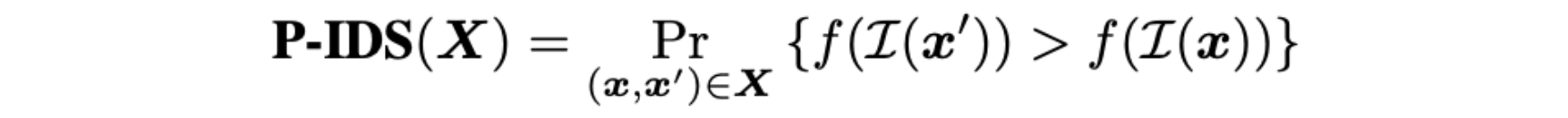

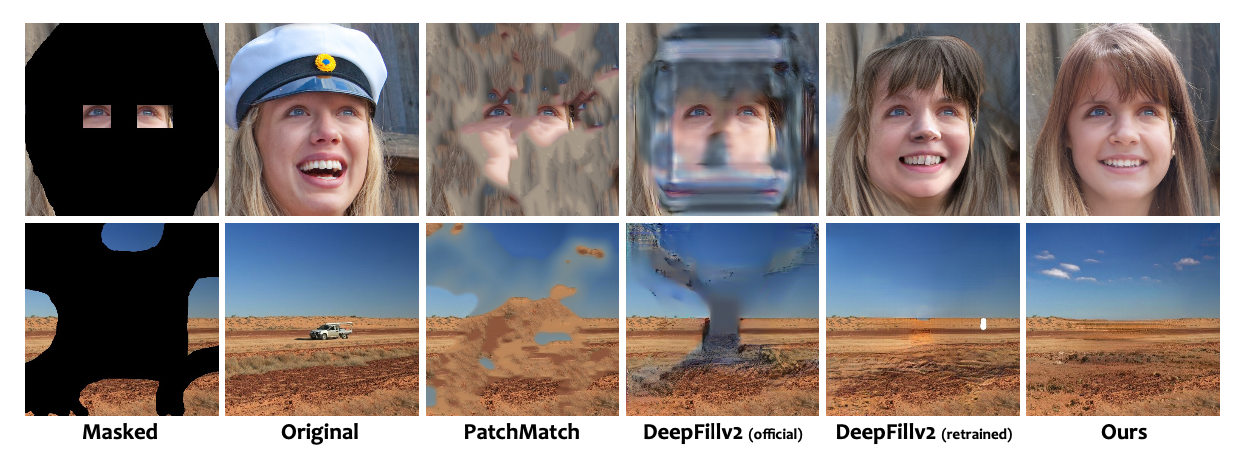

Paired/Unpaired Inception Discriminative Score

Evaluation methods are important for assessing the performance of GANs, but there is a lack of good quantitative metrics for image completion (Liu et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2019). Existing image completion algorithms rely on similarity-based metrics, such as PSNR and SSIM, but these approaches prefer blurry results that are less than ideal. As a result, qualitative metrics have been used, such as conducting a user study that asks humans to identify real vs. fake images. However, this approach lacks reproducibility and is time- and labor-intensive.

To address these challenges, Zhao et al. propose a new quantitative evaluation metric called Paired/Unpaired Inception Discriminative Score (P-IDS/U-IDS) that is robust to sampling size and correlates well with human preferences. The P-IDS/U-IDS has advantages over the Fréchet inception distance (FID) because it is robust to sampling size, effective at capturing subtle differences, and correlates well to human preferences.

P-IDS/U-IDS calculates the linear separability in the pre-trained feature space of an Inception v3 model $I(\cdot)$ that maps an input image to output features of 2048 dimensions. In the paired case, we have pairs of real images and their respective generated fake images $(x, x’) \in X$, where $x$ is the real image and $x’$ is the fake image. Features are extracted from an equal number of real and fake images and then fitted by a linear SVM, which represents the linear separability in the feature space. Let $f(\cdot)$ be the decision function of the SVM, and $f(I(x)) > 0$ if and only if $x$ is considered real. The P-IDS determines the probability that a fake image is considered more realistic than its corresponding real image, and it is given by:

Similarly, in the case where we do not have pairs of real and fake images, we sample an equal number of real images (from distribution $X$) and fake images (from distribution $X’$) and fit the linear SVM $f(\cdot)$. The U-IDS determines the misclassification rate, and it is given by:

Experiments

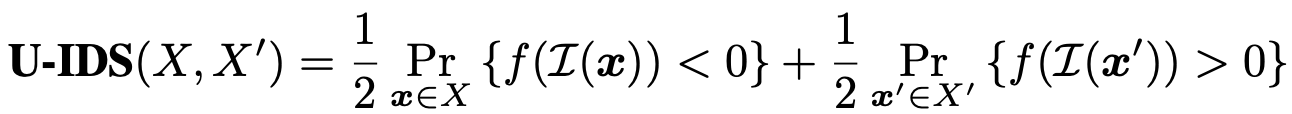

Image Completion

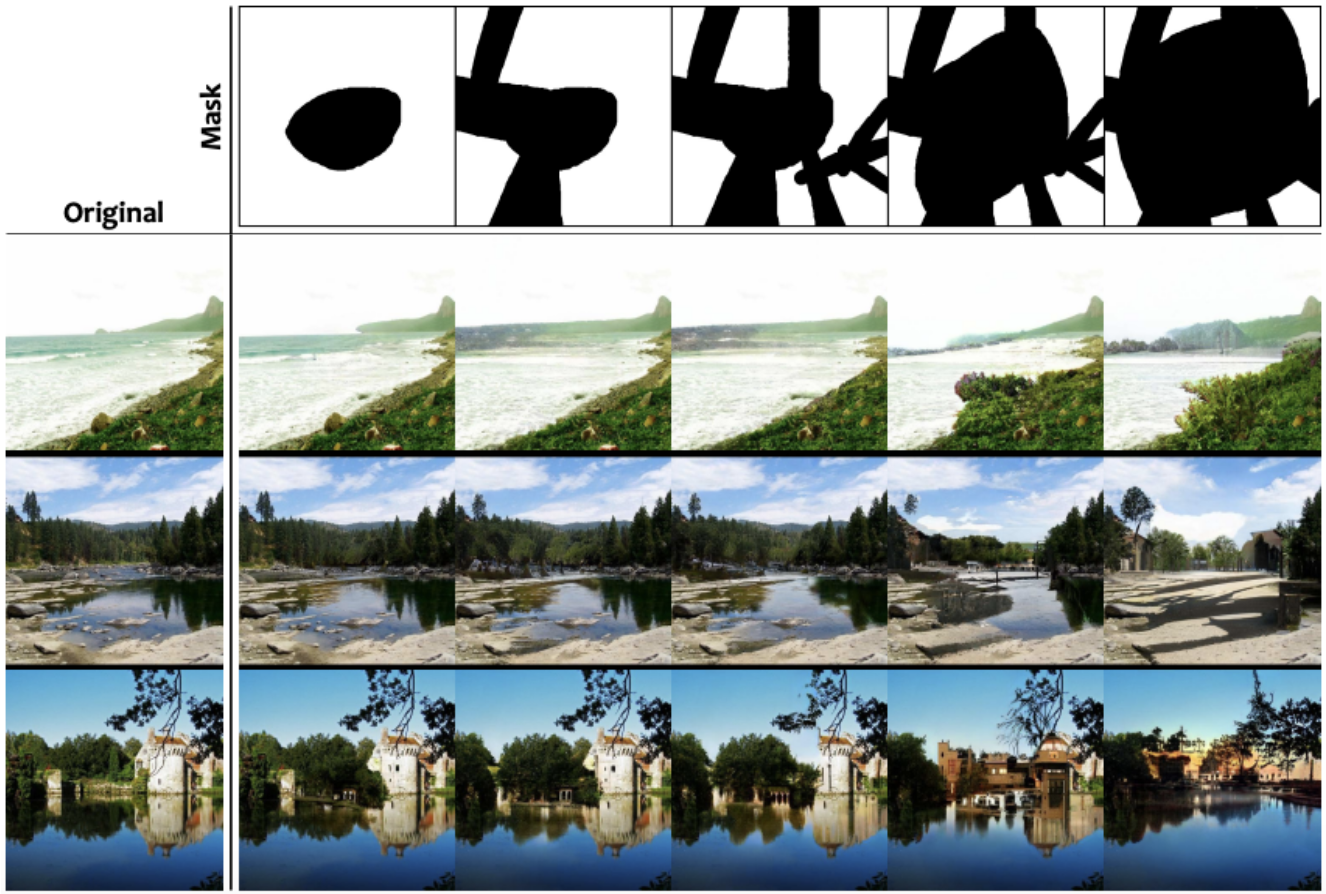

To use a co-modulated GAN for image completion, the model takes in as input a real image and a mask image that represents missing image regions, and it outputs a generated fake image that fills in the missing regions. The masks can cover any shape of the real image, including the entire image. To try a demo of co-modulated GANs, visit https://comodgan.azurewebsites.net/en-US/.

Zhao et al. conducted image completion experiments using the FFHQ dataset and the Places2 dataset. They compare the performance of using a co-modulated GAN with the performance of other state-of-the-art methods such as DeepFillv2.

Below are quantitative results for large scale image completion compared to DeepFillv2 and RFR.

Effect on Mask Shape on Generated Images Using Places2

Extending the work of Zhao et al, we investigated whether co-modulated GANs exhibit shape bias and evaluate the difference between the generated object and the masked object. Given an input image, we first create a semantic segmentation, using the model trained on the MIT ADE20K dataset. Then, we separate the segmentation out into its individual predicted classes and create a mask from one of the top predicted classes. Using the co-modulated GAN pre-trained on the Places2 dataset, we generate new images from the input image and the mask from the segmentation. The figure provides an example of the setup of this experiment.

Below is a sample of image generations from an image from the Places2 dataset with a mask on the swimming pool. The results lack diversity and fail to generalize that the shape of the pool is the shape of the pool mask. The results do show some semantic understanding that there would be a body of water in this region and consistently generates a pool of a certain shape that’s not the shape of the mask.

When using the co-modulated GAN trained on the Places2 dataset, generated images may fail to generalize object generation to the segmented shape, but the co-modulated GAN does show some semantic understanding of the class of object of the masked region. In addition, there is very little diversity among the set of generated images.

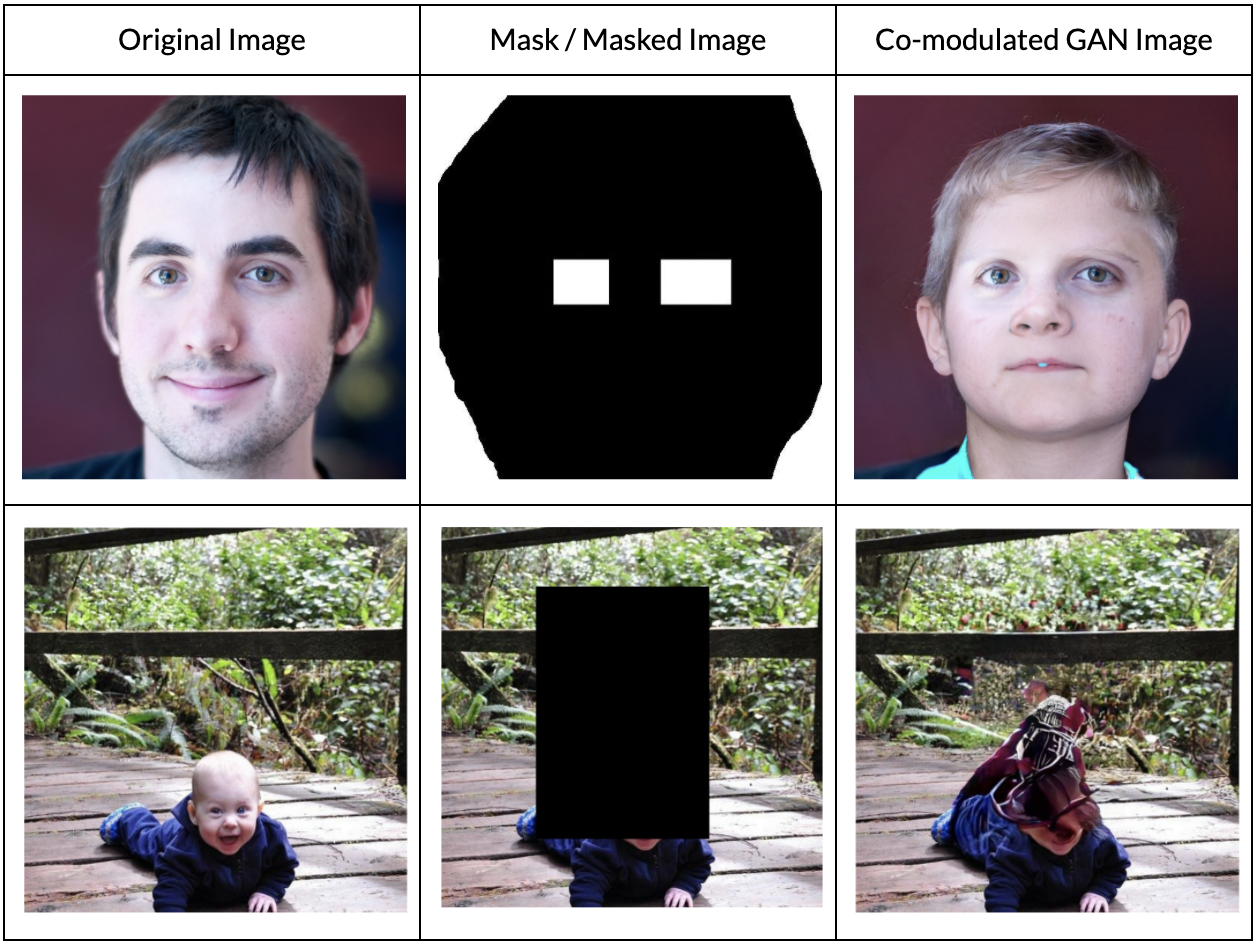

Examining the Distribution of Color in Completed Regions Using FFHQ

We extend the experiments by Zhao et al. by examining whether co-modulated GANs have color biases in the generated images. For our experiment, we sample 40 fake images using a given real image from the FFHQ dataset, and we use a mask that aims to cover a person’s shirt by masking the bottom one-fourth of the image. Then, we assess visually the diversity of the distribution of shirt colors in the generated fake images by calculating the number of fake images with shirts of different colors. We chose this evaluation approach because we need to determine the color in specific image regions that contain the person’s shirt, and existing approaches do not solve this task. The figure below shows an example of a real image and mask that was used for this experiment.

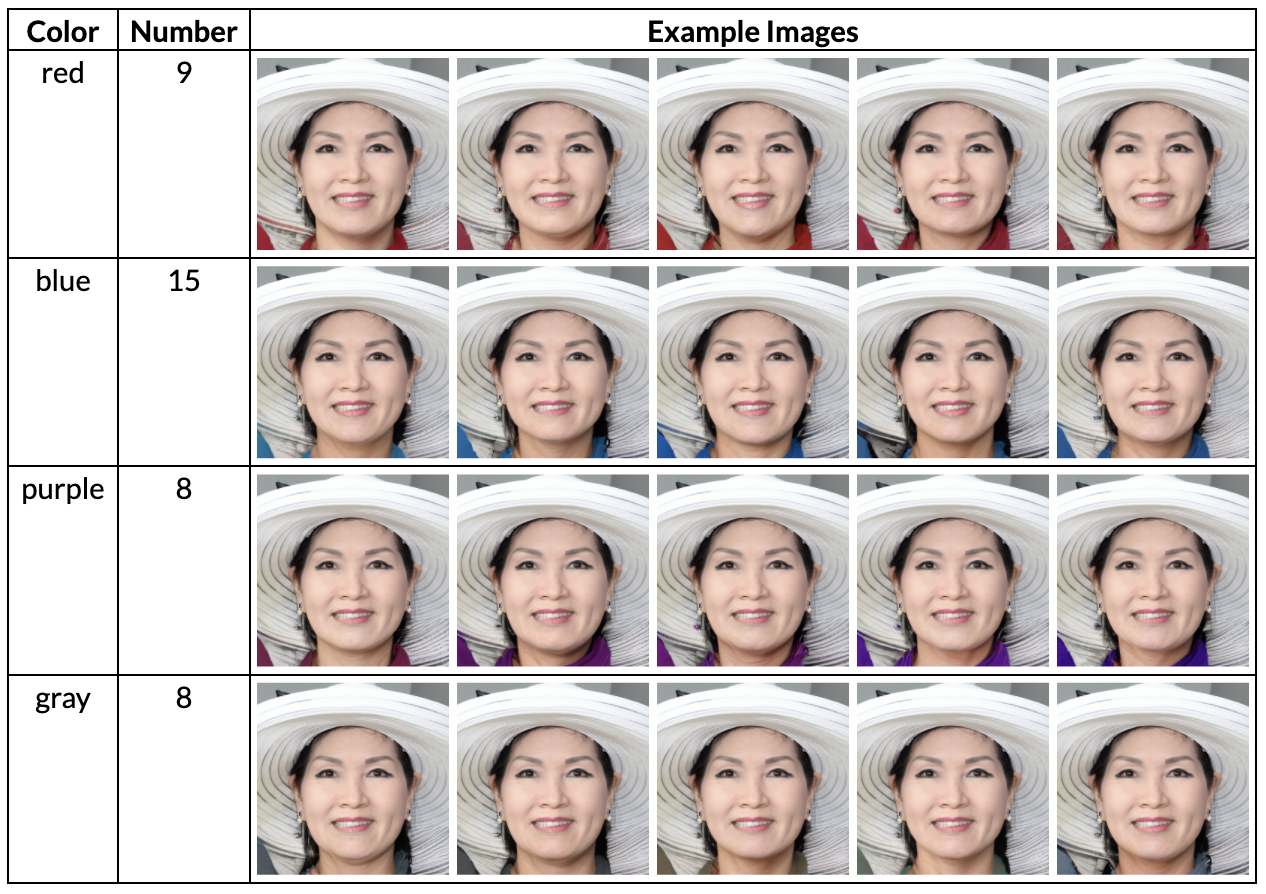

The person in the real image of the above figure wears a solid yellow top, which is covered completely by the mask. Since there is no indication of yellow clothing in the masked image, we expect that the co-modulated GAN produces fake images with differently colored clothes for the person. To determine the distribution of images, we grouped the shirt colors of fake images into one of nine possible colors: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple, black, gray, and white. The table below shows the distribution of shirt colors in the fake images.

We observed that the 40 sampled images for this specific real image contained only red, blue, purple, and gray shirt colors. An interesting next step would be to determine why the co-modulated GAN tends to generate images with these colors. In addition, the generated shirts all contained one solid color. Examples of fake images for each of these colors are included in the table.

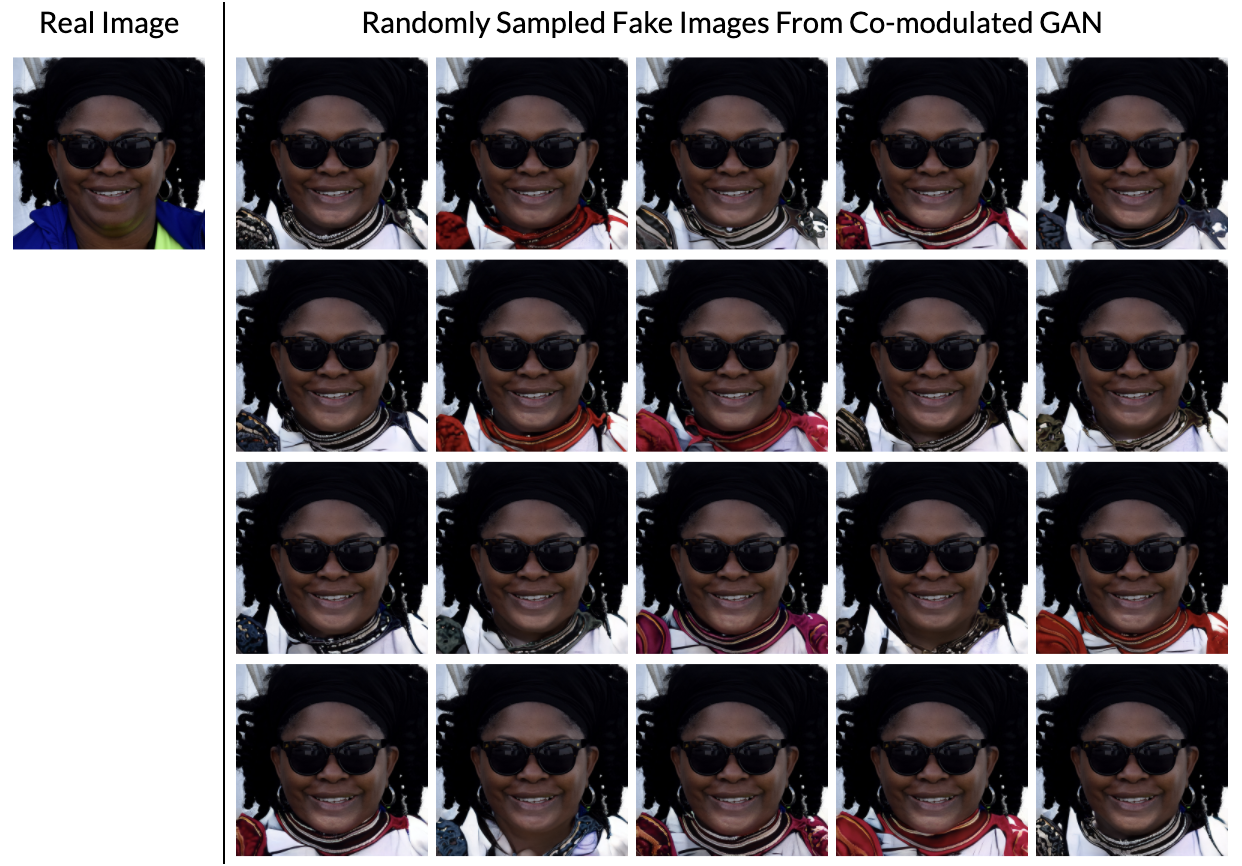

Another example of this experiment uses the real image in the figure below, which contains a person wearing solid blue and green clothing. In contrast, we see that most of the generated images contain non-solid colors that are not blue or green and contain very similar shirt designs. Because the shirt colors are not solid, it is difficult to categorize them into specific colors. Instead, we display 20 of the 40 sampled images.

We noticed that a significant number of the shirt colors contain white and designs with red, blue, gray, and brown-like colors. The amount of white in this color distribution could be influenced by the white background color, but it is uncertain why the non-white colors and generated designs in the masked region of the image are less diverse.

Image-To-Image Translation

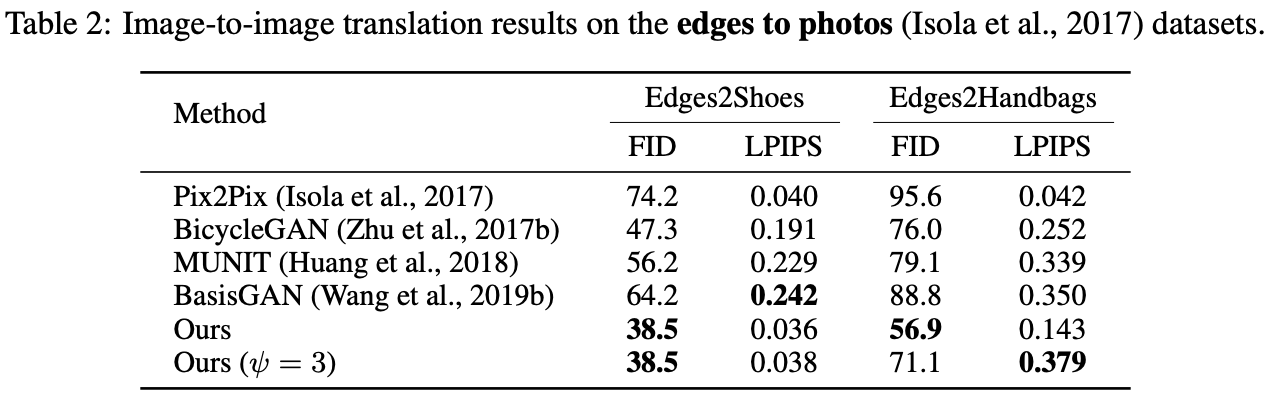

Since co-modulated GANs are generic image-conditional models, they can be easily extended to image-to-image translation tasks. Zhao et al. perform image-to-image translation experiments on the Edges2Handbags dataset and the Edges2Shoes dataset.

Using a co-modulated GAN results in higher fidelity (FID) over state-of-the-art methods on these edges to photos datasets. The model also produces superior diversity on the Edges2Handbags dataset, but it does not learn to generate diverse images on the Edges2Shoes dataset. The table below compares the performance of the co-modulated GAN with other methods.

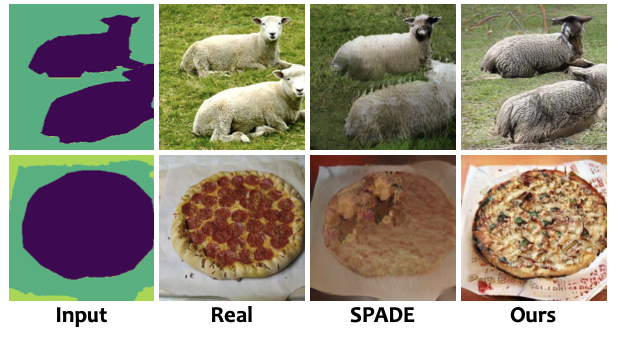

The images below include results from the image-to-image translation task on the COCO-Stuff validation set using SPADE and co-modulated GANs.

Biases and Limitations of Co-modulated GANs

Large-scale image completion is a difficult task. While the co-modulated GAN is able to produce diverse and high quality results in image completion and generalize easily to image-to-image translation, there are still several limitations to the model. Sometimes the model underperforms in recognizing semantic information, particularly in the Places2 dataset, which contains millions of different scenes. As a result, strange artifacts may appear. In addition, some objects from generated images are more diverse within the object class while other objects converge to generating a certain type of object. For example, masked regions in natural sceneries tend to generate similar images, whereas masked regions on buildings tend to have a wider variety of generated objects. While the co-modulated GAN incorporates stochasticity and generalization, it’s difficult to find the right balance.

The figure below shows examples of images generated using the co-modulated GAN and FFHQ dataset for the image completion task. As the mask covered up more of the image, there were noticeable changes in age, race, and gender as well as facial expressions, clothing, and accessories from the generated image to the input image. Specifically, we see that the generated images tend to include red colors that are not present in the original images. This aligns with the findings of our experiment studying the distribution of colors among generated images in the previous section.

We also noticed that there are sometimes unusual artifacts added to images, and other failure cases may occur. For example, in the top row of images in the figure below, the generated image includes bright blue-green artifacts to the person’s face near the nose and mouth. This blue-green color appears to be the same color that is added to the person’s clothing in the image. In the second row of images, the co-modulated GAN fails to recreate an image of the young child.

Related Work

Image Completion

Image completion can be viewed as a constrained image-to-image translation problem. Early works for image completion used low-level features and could not generate semantically consistent contents. With the rise of deep neural networks, we have seen improvements in image completion tasks. Then, the work by Pathak et al. on Context Encoders gives rise to the first conditional GAN.

Many follow-up works improved on semantic context and texture, edges and contours, and various architectures. Later works focused on the lack of stochasticity and image outpainting subtasks.

Image-To-Image Translation

Image-conditional GANs can be applied to many image-to-image translation tasks. pix2pix uses a conditional adversarial network that learns both the mapping from input to output image and the loss function to train this mapping. As a result, this network has a wide applicability to various image-to-image translation problems, such as semantic labels to photo, black and white to color, edges to photo, day to night, and aerial to map, without the need for extra parameter tweaking.

Conclusion

Overall, co-modulated GANs are a promising approach for large-scale image completion tasks. In this blog, we presented an overview of co-modulated GANs, the proposed P-IDS/U-IDS quantitative metrics, and results from the paper by Zhao et al. We also performed new experiments investigating the effect of mask shape on generated images using the Places2 dataset, as well as the distribution of color in completed regions using the FFHQ dataset. In addition, we found interesting biases and limitations of using co-modulated GANs on some images in the FFHQ and Places2 datasets, such as the tendency to generate images with red colors.