Attention Solves TSP

09 Dec 2021 | Traveling Salesman Problem Combinatorial Optimization Attention NetworkThis post discusses a recent publication at ICLR 2019 [Kool et al., 2019] on applying attention layers for solving the well-known combinatorial optimization problem, Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP).

On the other hand, this post is inspired by a recent research challenge held by Amazon, Amazon Last Mile Routing, where the author participated with two excellent teammates Qingyi Wang and Baichuan Mo. The challenge encourages paticipants to develop innovative approaches leveraging non-conventional methods (e.g., machine learning) to produce solutions to the route sequencing problem, which could outperform traditional, optimization-driven operations research methods in terms of solution quality and computational cost.

As a part of the exploration process for competing in this challenge, author’s team implemented the attention-based model proposed by Kool et al. and gained insights on how the proposed model performed on real-world routing problems. The author will summarize the attention-based model and discuss its performances on real-world instances and comparisons with traditional optimization-driven methods.

Background

Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP)

The Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) is a traditional combinatorial optimization problem, which is also an NP-hard problem that can not be solved with polynomial time algorithms. The TSP requires to find the shortest distance route that visits all given locations and return to the original location.

Figure 1. TSP instance

Figure 1. TSP instance

TSP is typically solved with optimization-driven approaches where TSP is modelled as an Integer Linear Program (ILP) and solved with off-the-shelf ILP solvers, e.g., Gurobi and CPLEX. However, large-scale TSP instances can not be solved optimally with solvers. Therefore, many researchers have focused on developing heuristics to solve the large-scale TSP instances, where their proposed algorithms are not guaranteed to be optimal. Some interesting real-world solved large-scale TSP problems can be found here. For instance, an optimal TSP tour to visit 49,687 pubs in UK have been found through optimization-driven methods.

DNN to solve TSP

On the other hand, the success of DNN in the past decade has drawn the attention of applying the DNN into solving the combinatorial optimization problem.

Vinyals et al. [Vinyals et al., 2015] introduces the Pointer Network (PN) to solve the offline TSP with the supervision of optimal solutions, where attention is used to output a permutation of the input sequence.

Nazari et al. [Nazari et al., 2018] replaced the LSTM encoder of the PN with element-wise projections and applied the proposed model to genralizations of TSP, Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP) with split deliveries and a stochastic variant.

Kaempfer et al. [Kaempfer et al., 2018] proposed a model based on the Transformer architecture [Vaswani et al., 2017] which outputs a fraction solution to the multiple TSP. The fraction solution can be treated as an LP relaxation of the ILP problem and they recover the integer solution via a beam search process.

Attention Mechanisms and Transformers

The main idea under the proposed attention-based method for solving the TSP is taken from the Transformer architecture proposed by Vaswani et al. [Vaswani et al., 2017]. The Transformers are constructed based on attention mechanisms, where stacked self-attentions are conducted in both encoder and decoder. The proposed attention-based TSP approach adapts the Transformer architecture into solving TSPs with minimal adjustments.

Model Structure and Training Algorithm

For the TSP, let $s$ be a problem instance with $n$ nodes, where node $i \in {1,…,n}$ is represented by a feature vector $x_i$ (a vector of coordinates). Let $\boldsymbol{\pi} = (\pi_1,…,\pi_n)$ as a solution tour, which is a permutation of nodes. The attention-based encoder-decoder model defines a stochastic policy $p(\boldsymbol{\pi} \mid s)$ for a selecting a solution $\boldsymbol{\pi}$ given a problem instance $s$. It is factorized and parameterized by $\boldsymbol{\theta}$ as

\[\begin{equation} p_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{\pi} \mid s) = \Pi_{t=1}^n p_{\theta}(\pi_t \mid s, \pi_{1:t-1}). \end{equation}\]As indicated in the stochastic policy, the encoder produces embeddings of all input nodes and the decoder produces the sequence $\boldsymbol{\pi}$ of input nodes on at a time. Detailed architecture for encoder and decoder are introduced in the following sections.

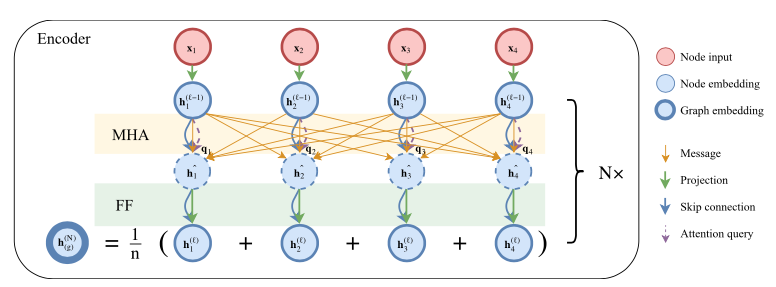

Encoder Structure

The encoder is similar to the encoder designed by Vaswani et al. [Vaswani et al., 2017] except the positional encoding is ignored such that the node embeddings are invariant to the input orders in TSP. The embeddings are updates using $N$ attention layers. The encoder computes an aggregated embedding $\bar{h}^{(N)}$ of the input graph, which is the mean of the final node embeddings $h_i^{(N)}: \bar{h}^{(N)} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n h_i^{(N)}$. And all node embeddings and graph embedding will be used as the input for decoder. Figure 2 shows the detailed encoder structure.

Figure 2. Encoder Sturecture

Figure 2. Encoder Sturecture

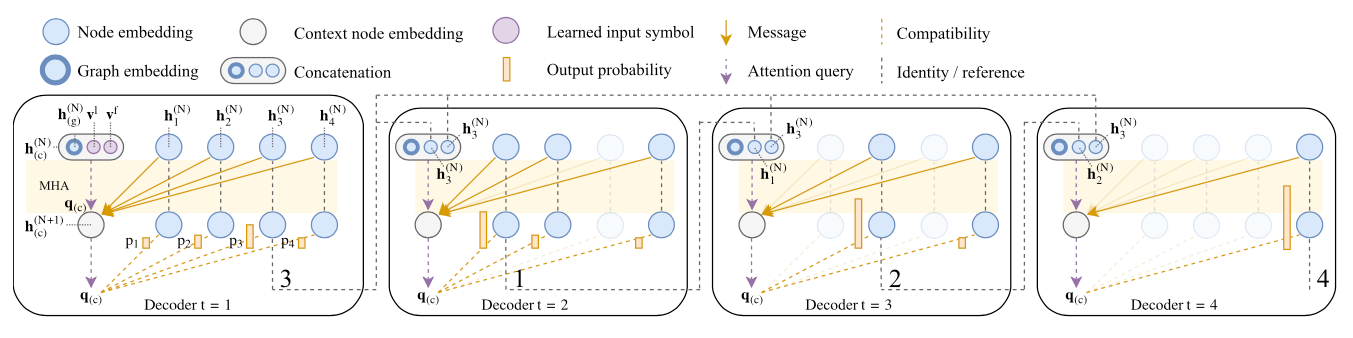

Decoder Structure

For the decoder, it generates the solution route sequentially during each time step $t \in {1,…,n}$. At time $t$, the next visited node is generated based on the embeddings from the encoder and the outputs $\pi_{t’}$ generated at previous time periods $t’ < t$. In the decoding process, we introduce a context node to indicate the decoding context, which is a concatenation of graph embeddings, node embeddings of first node and previous visited node. When moving to the next time period, the visited nodes are masked in the graph. Figure 3 shows the detailed decoder structure.

Figure 3. Decoder Sturecture

Figure 3. Decoder Sturecture

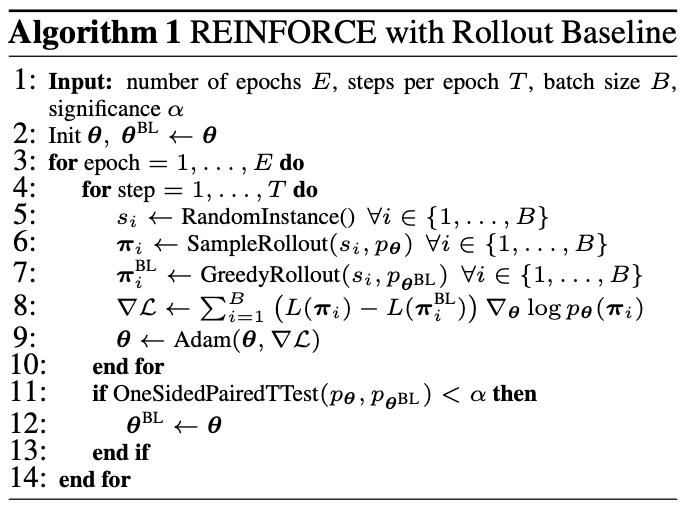

Training Algorithm

To train the attention model for solving the TSP, we need to specify the loss function. The objective function of the TSP is to find the route with the minimum cost. Therefore, the loss function can be defined as the tour length for the solution path, represented by $L(\boldsymbol{\pi})$. Given a stochastic policy $p_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{\pi} \mid s)$, the loss function is

\[\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\pi} \mid s) = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{\pi} \mid s)} \left[ L(\boldsymbol{\pi}) \right]. \end{equation}\]The loss function $\mathcal{L}$ is then optimized by gradient descent using the REINFORCE gradient estimator with baseline $b(s)$:

\[\begin{equation} \triangledown \mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\pi} \mid s) = \mathbb{E}_{p_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{\pi} \mid s)} \left[ (L(\boldsymbol{\pi}) - b(s)) \triangledown \log p_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{\pi} \mid s) \right]. \end{equation}\]The key of this traning algorithm is to choose a good baseline $b(s)$, which can reduce gradient variance and increase the training speed. In the attention-based TSP model, a greedy rollout baseline model is utilized where the model is trained to improve over its self. The detailed training algorithm is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Training algorithm

Figure 4. Training algorithm

Experiments

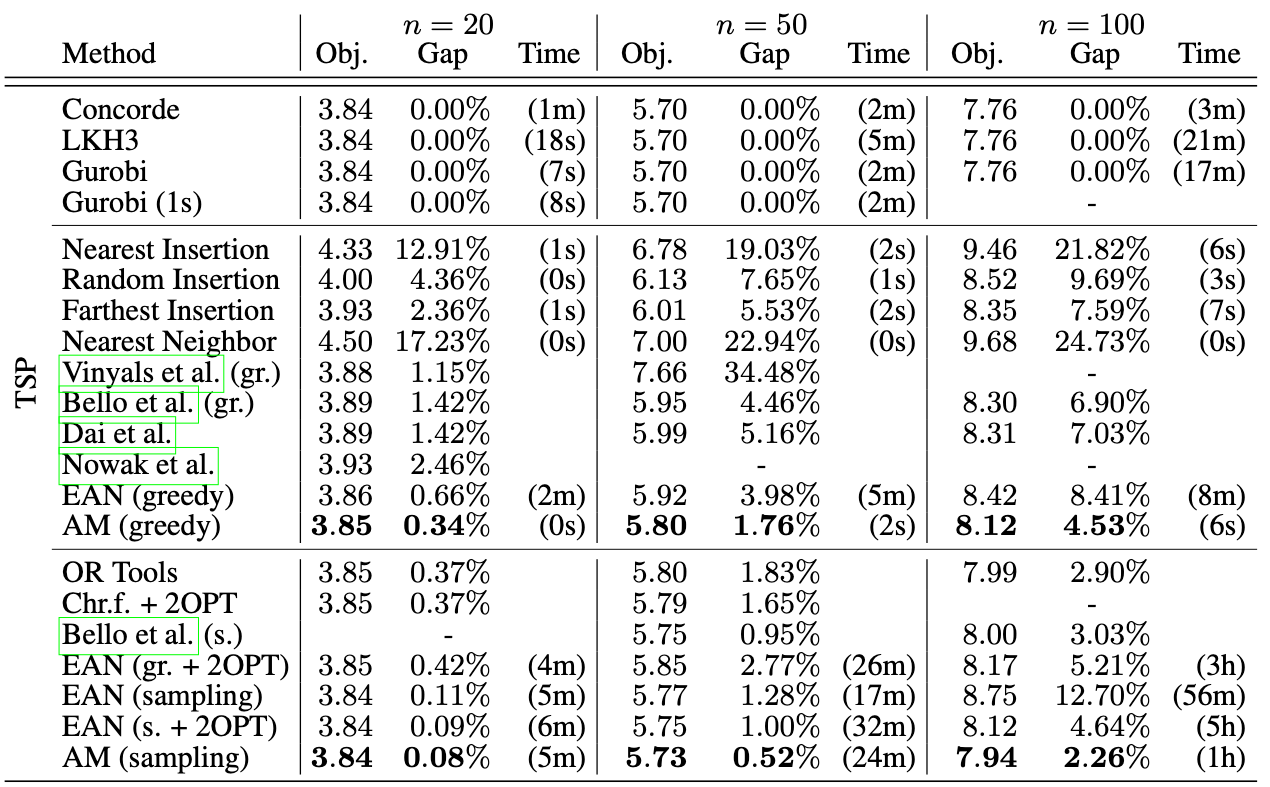

In this section, only comparison results with TSP will be shown. More results regarding multiple generalizations of TSP can be found in the original paper. The code for conducting experiments can be found here.

Figure 5 shows the comparison results on solving TSP. The attention-based model is compared with optimization-driven models, naive heuristics and existing DNN approach for solving TSP. For the optimization-driven approach, it considers two solvers, Concorde and Gurobi, and a state-of-the-art heuristic solver, LKH3. Regarding heuristics, nearest insertion, random insertion, furthest insertion and nearest neighbor are utilized. All methods are tested with three different instances with different sizes: $n=20, 50, 100$. Attention Model (AM) outperform other heuristic-based approaches and DNN-based approaches regarding optimality gap. It can have a close performance compared to the optimal scenario solved by optimization-driven solvers. Meanwhile, the computation time is significantly decreased when using AM compared to optimization solvers.

Figure 5. TSP Results

Figure 5. TSP Results

Discussions

The proposed Attention model works well when having a rich dataset or training instances which can be generated randomly. The training data consists of a list of nodes with coordinates and travel distance between any two nodes. The training process of the model requires over 1 million TSP instances. For the Euclidean TSP, coordinates can be generated randomly and distance matrix can be calculated easily. For the metric TSP, we can sample the instance based on a list of locations with coordinates and a distance matrix between any two locations. It requires extra computational task for generating the distance matrix. However, it is still computationally feasible.

The advantage of the proposed method compared to the traditional optimization approach is the short computation time for getting routes with good performances (close to the optimum). Training the model requires a lot of time, but it can be done offline. It is suitable for the scenario where decision makers need to make routing decisions within a short period of time. Also, giving more training data and training time, trained model can have better performances with smaller optimality gaps. Therefore, applying state-of-the-art DNN approaches to traditional combinatorial optimization problems is a promising direction to explore.

As for the Amazon Last Mile Routing Challenge, it requires to learn the routing sequences from experienced drivers given a list of locations need to be visited. To apply the attention-based model, we need to modify the loss function in the model. We tried two different loss functions: similarities between drivers’ sequences and trained sequences, and travel cost between two types of sequences. The training data provided by the Amazon is around 5000 instances. We trained the model with both loss functions and did not achieve competitive performances compared to routes simply generated by implementing a TSP solver, where routes with minimum cost are generated.

The main reason for the poor performance in this scenario is because the training dataset is not large enough. However, the loss function requires the knowledge of routes from experienced drivers, which can not be generated given any random TSP instances. The lack of training data leads to poor trained model. To achieve a relatively good performance, we need at least 10 times more data than the data provided currently. However, routes from experienced drivers are valuable information that can only be gathered over time. Therefore, DNN-based approaches are not appropriate for the Amazon Challenge even if the challenge encourages competitors to use non-traditional approaches for solving problems related to TSP.

Overall, the attention-based model is a powerful tool to solve the large-scale routing problem with clear pros and cons. The key success for applying such models is to have enough high-quality data to train the model. Therefore, when applying advanced deep learning methods into solving the combinatorial optimization problem, more focus should be put on how to generate a large set of high-quality data within a reasonable amount of time with the help of traditional optimization approaches.